The following is a simplified version of a paper I wrote back in 2018 while completing my Master’s in Game Design. I’ve been holding off sharing this for a while because I was hoping to publish it in a journal someday, but I’ve decided I don’t want to wait around any more and would rather just put it out into the world. I would love to hear your thoughts on this, so let me know what you think in the comments below.

TL;DR Roguelikes are games with Procedural Content and Permachoice, but we should revisit this definition in a few years to see if it is still true.

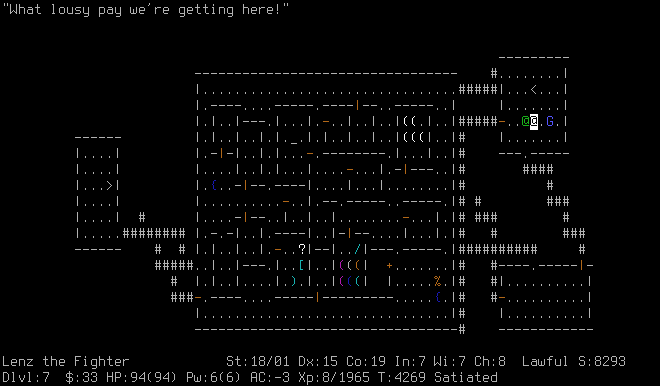

Rogue, A.I. Design, 1980

When it was originally released in 1980, no one could have expected Rogue: Exploring the Dungeons of Doom to inspire an entirely new genre of video games. Rogue, as it is more often called, is a Unix-based dungeon-crawler created by Michael Toy, Glenn Wichman, and Ken Arnold. Inspired by the text-based adventures and roleplaying games of the time, players delve deeper and deeper into a procedurally generated dungeon to retrieve the Amulet of Yendor. Though the game was not a dramatic financial success, it was very popular and inspired numerous other games including NetHack, Angband, Crawl, and ADOM. These “Roguelikes,” as they would come to be known as, are still very popular today. But what exactly is a Roguelike? Surprisingly, the definition of a Roguelike has been a highly contentious and debated topic for over two decades.

The first documented attempt to define Roguelikes was in this Usenet post made in 1993. Though it was uncertain what exactly to call the genre, it argued that the key characteristics of the genre are that it is character-based and very portable (meaning it can be ported onto many different systems). The genre continued to be vaguely defined until 2008 when Santiago Zapata proposed 13 “Roguelikeness” factors to describe how Roguelike a game was. These factors were divided into High-Value Factors (such as Random Environment Generation and Permafailure), Medium-Value Factors (such as Single Player and Plenty of Content), and Low-Value Factors (such as High Ramped Difficulty and Monsters as Players). This definition did not define the distinction between High, Medium, and Low-Value factors, nor did it describe how many of these traits are required to be considered a Roguelike. However, this definition would be the basis of the most important and contentious definitions of Roguelikes: The Berlin Interpretation.

What is the Berlin Interpretation?

High-Value Factors

Random Environment Generation

Permadeath

Turn-Based

Grid-Based

Non-Modal

Complexity

Resource Management

Hack’n’Slash

Exploration and Discovery

Low-Value Factors

Single Player Character

Monsters are Similar to Player

Tactical Challenge

ASCII Display

Dungeons

Numbers

Created at the International Roguelike Development Conference in 2008, The Berlin Interpretation of Roguelikes intended to create a definition for Roguelikes beyond just that they are “like-Rogue.” It used what they considered to be the canon for Roguelikes (ADOM, Angband, Crawl, NetHack, and of course Rogue) as well as Zapata’s Roguelikeness Factors to establish its own 15 Roguelike factors (which you can see outlined on the left). Similar to the Roguelikeness Factors, these traits were divided into High-Value Factors (such as Random Environment Generation, Permadeath, and Complexity) and Low-Value Factors (such as ASCII Display and Dungeons). The Berlin Interpretation does not state how many of these traits are required to be considered a true Roguelike and claims that the purpose of the definition is “…for the roguelike community to better understand what the community is studying. It is not to place constraints on developers or games.”

Since its inception, the Berlin Interpretation has become the default definition for Roguelikes. However, since 2008, there have been countless “Roguelikes” released that may or may not fit this definition. Sometimes referred to as “Roguelites” or “Roguelike-likes,” games such as Spelunky, Don’t Starve, Rogue Legacy, FTL, and The Binding of Isaac combine elements of Rogue with other gameplay elements to create games that seem to test the limits of the genre. But based on the Berlin Interpretation, are these games still Roguelikes?

Does the Berlin Interpretation still hold up? Well…

Spelunky, Mossmouth, 2013

When you look at many of the most prominent and popular “Roguelikes” and “Roguelites” released since 2008, almost none of them possess all 15 traits identified in the Berlin Interpretation. ASCII Display in particular is especially uncommon today. To be fair, many of its traits are very common in modern Roguelikes, such as Random Environment Generation, Complexity, Resource Management, Hack n’ Slash, Exploration and Discovery, and Tactical Challenge. But for some traits, it’s not clear how common it is. Permadeath, one of the most commonly cited core traits of Roguelikes, is so vaguely defined that it is hard to tell what it means. In most modern Roguelikes, when a character dies that character is no longer useable. However in many of these games, such as Slay the Spire, Dead Cells, Darkest Dungeon, Enter the Gungeon, Hades, and Crypt of the Necrodancer, there exists some form of progression outside of individual play sessions, such as unlockable items or permanent upgrades. Therefore, it is unclear whether these games possess Permadeath since there exists a meta-progression between gameplay sessions.

So if many modern Roguelikes do not possess all these traits, does that mean that none of them are Roguelikes? I would argue no. Rather, I believe the problem is with the definition itself. The Berlin Interpretation was created over a decade ago, and since then the genre has changed and evolved. As a result, the definition is out of date and out of touch with modern Roguelikes and is written far too exclusionary. Many of its factors are either too arbitrary, too vague, or too specific. Additionally, the Non-Modal factor doesn’t even encompass ADOM, Angband, and Crawl, all games which it claims belong in the Roguelike canon. When taken together, this shows that the Berlin Interpretation doesn’t define what makes a Roguelike a “Roguelike,” but rather what makes the game Rogue “Rogue.” Because of this, we have no choice but to reject the Berlin Interpretation and instead find an alternative definition.

What are the alternative definitions for Roguelikes?

Since 2008, a few people have proposed their own definitions for what a Roguelike is, although none of them have gained the notoriety of the Berlin Interpretation. The Traditional Roguelike definition cut down the 15 factors to only four: Permanent Consequences, Character-Centric, Procedural Content, and Turn-Based. While certainly a dramatic improvement over the Berlin Interpretation, it is still too narrow to encompass all Roguelikes under a single definition. Instead, as Zapata said, it aims to keep the original historical meaning of the genre. While preserving the genre’s roots is admirable, forcing Roguelikes to adhere to their origins will cause the genre to stagnate, or worse die out completely.

Tom Cadwell gave this talk at GDC where he somewhat indirectly proposed that Roguelikes require mastery loops (a cycle of failure, learning, and success), a diverse range of tools with inconsistent availability, competing objectives that require strategic commitment, and lots of variety. While I do think that Cadwell gets much closer to the heart of what makes a Roguelike a Roguelike, his criteria are a bit too vague to be useable as a concrete definition.

The Modern Definition of Roguelikes

Based on these definitions, as well as my analysis of modern Roguelikes, there seem to be two key traits that are consistent across all Roguelikes. I will refer to these traits as Procedural Content and Permachoice. Procedural Content refers to procedural generation, meaning that the game’s content is randomly generated each time that it is played so that no two play sessions are identical. This forces players to utilize their creativity and problem-solving skills in order to succeed using the tools at their disposal.

Permachoice means that the outcomes of a player’s actions (both positive and negative) cannot be undone. This means that players cannot reload old save files to undo their poor choices, often including death. By framing this trait as “Permachoice” rather than “Permadeath,” we can still allow for games that contain meta-progressions between gameplay sessions, so long as decisions made in those meta-progressions cannot be undone. This is meant to encourage tactical play, meaningful decision making, and a cycle of learning from previous mistakes.

I propose that these two factors, Procedural Content and Permachoice, should form the current definition of a Roguelike. These two qualities both encompass all current Roguelikes and provide adequate space for the genre to continue to evolve. However, this definition comes with two main caveats. First, this definition is not immutable. Given that the Roguelike genre is still changing, alternative traits may emerge over the next few years that offer a better basis for the genre. As a result, this definition is intended as the current working definition and should be revisited in the future.

Second, Roguelikes should be treated as a modular genre. As defined by Adam Millard in their video on the topic, a modular genre is a genre that can be combined with other genres to give a more accurate description of a game. For example, The Binding of Isaac would be a Real-Time Action Roguelike, Crypt of the Necrodancer would be a Semi-Real-Time Rhythm Roguelike, and Dream Quest would be a Turn-Based Deckbuilding Roguelike. By treating the Roguelike genre as modular rather than all-encompassing, it allows us to describe them with more nuance and better categorize and curate them based on our needs.

Roguelikes are a deeply engaging and unexplored genre. Though they have changed a lot since their beginnings in the 1980s, the recent innovations in the genre over the past decade show us that it is not done evolving. By moving away from the Berlin Interpretation and instead defining Roguelikes as a modular genre which feature Procedural Content and Permachoice, we can both understand and study the genre while giving it the freedom to continue to produce unique and innovative games.